Since his birth in Mansoura (some 140 km north of Cairo) to two Egyptian parents, 19-year-old programming engineer, Sameer Ali (pseudonym) only has his birth certificate, his first proof of citizenship.

Ali is supposed to have a compulsory military service certificate (completion or exemption), before reaching the age of 30. He cannot officially embark on his practical career before obtaining this military service certificate, because it is officially required in employment qualifications in both the public and private sector. It is also required when applying for ID cards and passports.

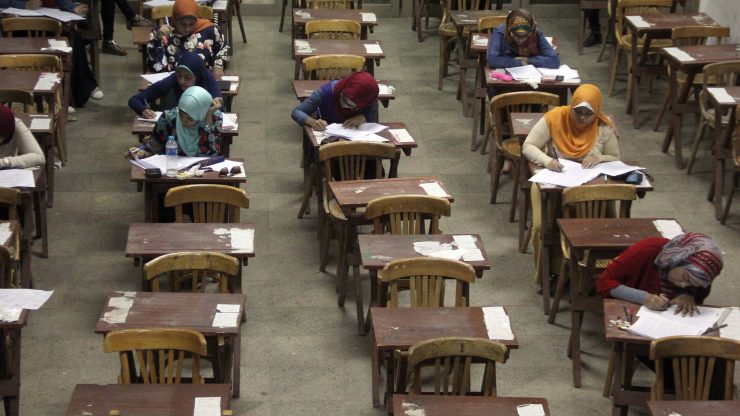

Between the birth certificate and military certificate, an Egyptian will obtain no less than three educational diplomas after going through a strict and inflexible system.

How the system works

Three offices and one center (civil registry office, coordination office, mobilization and recruitment center, and workforce office) determine the career path.

A male child is born and has two options after finishing his basic education. The first shorter option is to go through technical and vocational training, while the longer one is to go through secondary and university education. After that, all ways will lead to completing military service, unless he joins higher education via an admission coordination office in Egyptian universities, to finish his education and military service. Only after that, will the government offer him a job through the Ministry of Manpower.

Leaving the educational system

Population growth and subsequent increase in job seekers applied huge pressure on workforce management in Egypt. This was associated with an emergence of other tracks and options that rely on self-learning provided online, which in turn created a new labor market. Ali took one of these tracks. When he completed 10 years in 2009, Egypt’s population was more than 76 million, with an increase of about 15 million (25%) from the last census in 1996. That increase was beyond the capacity of the old-fashioned system, defined by the three aforementioned offices. While reliance on work force offices decreased, labor market was liberalized with the development of private sector, and flourishing of communications and Internet systems in Egypt. In parallel, a new Internet-based job market emerged. Therefore, many training and learning centers were established to cater for prospective market requirements, and teach new programming languages.

In 2011, Sameer, who was 12 years old, took his first step in learning programming. Two years later, he began working as a freelance programmer for several small web projects. He had two choices to pursue his professional career: either to continue his regular studies in high school, university, complete his military service, to start looking for a job in a fast-developing market, or to join the labor market directly with his growing experience in programming.

“I joined a market that depended on skills rather than official certificates,” he said. He moved from his home city of Belqas (140 km north of Cairo) in June 2013 to Cairo to work for a company specialized in technical solutions, website design, and management. In four years, he moved between five promising and well-known companies in the field of communications and built a successful professional reputation within this field with a relatively high monthly income.

Educational delay in lieu of military service

Young people are required to enlist in military service once they have reached 19 years of age, unless they join a school or university.

Official education in Egypt, says Yousef Hassan (pseudonym), is currently considered a means of deferring military service. Hassan is 23-year-old student in the third division at the Faculty of Commerce, Helwan University. He is a web programmer as well as an event organizer. He does not intend to graduate from the university at present, and considers a delayed graduation a better alternative to joining the armed forces. “My monthly income is good and stable, and I have a successful job,” he says. He adds that he is qualifying himself through free studies and online courses to improving his career, obtain required certificates to travel abroad, and run his own business without interruption.

Hassan realizes that his plans imply not having a university degree, but he believes that a person in his situation does not need it. “Employment is the purpose of learning, is not it?” he asks. “The last thing I need is to interrupt my private work to spend at least one year in military service.”

The risk of leaving the educational system

According to the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, at the ‘Census of Egypt’ conference, held on September 30, Ali, who did not continue his official education after his preparatory degree, is one of the 18.8% of 94.8 million Egyptians. According to this classification, Ali will be required to serve two years of compulsory military service, depending on his qualification, which is below medium level. During these two years, he will be away from a fast-developing field, and his career will be affected.

Ali, who works in a highly specialized profession, with five years of experience, has a good career, a below-medium level official certificate, and three diplomas from international centers and companies in his field of specialization, has a few options. Either he completes two years of military service, sacrificing a proven promising record of accomplishment, or he joins a different learning track, without a commitment to learning, only to postpone military recruitment. Other options include joining high school again – and interrupt work for two years – or avoiding military recruitment for an indefinite period.

Ali has a passport, but cannot travel without a military permit. He works with two technical solutions companies in Jordan and Arabian Gulf from his room in Cairo. He realizes whenever he moves inside or outside of Cairo that there is a possibility of being suspected, and taken to complete military service. Since his work is outside the official framework, it is not certainly subject to Egyptian labor law, and he has no guarantee of his rights as an employee, or taxes to pay like any working citizen.

A new path?

Both Ali and Hassan chose career paths that have existed for no more than 10 years in the market. In addition, their learning opportunities are not limited to official education systems in Egypt and their practice depends on skill, experience, and free learning rather than accredited governmental certificates.

They present a different reading of the Egyptian educational system as a long path that allows the learning of new skills outside its official framework, ends with a university certificate of social merit, and preserves the rights of its holder to act as a working citizen who exercises his duties and defers compulsory military recruitment.